The Fortress of the Subject

I do not discuss the individual, a word whose etymology reveals a familiar scope : the non-separated, the undivided, namely the now deified figure of the self-contained individual. At stake here is the subject, the animal capable of speech, who by virtue of language knows and views himself as being estranged from other animals, free of any mode reminiscent of animality. This vision of self, we shall call reflexive consciousness.

This consciousness of self leads up to human interlocution with oneself, and with the World. It is this defining feature of humanity that implies the solitude of the subject, as embarked on the “exhausting consciousness of being”, and staged within the Theatre of discourse upon which rests the function of instituting. The quote borrowed from the Russian author Turgenev could offer a judicious introduction to psychoanalysis, both accepted and banished as a discipline, as is fitting to approach the first anchor point for a dogmatic anthropology: to take into consideration the reason to live in the examination of the most fundamental – to institute Reason – inseparable from the mutual bond between subject and society.

No one chooses neither a time nor a place of birth, nor the authors of one’s birth. And whoever was able to glimpse into the palimpsest of families or into the montages of his own life has tasted the wild fruit. But what is to be done with life, in these Western societies now replete with overabundant knowledge laying claim to universality, pretending themselves foreign to the wild fruit ? Who will be able to civilize the human complaint, who will theatricalize the originating why in a decent manner, and rescue us from the dread of being transparent ? Who ? What I actually mean is : what discourse, with relevance to institutions ? That is to say, which discourse will be capable of reversing the great positivist impostures that threaten to once again set the whole humanity on fire ?

We are cut off from who we are. Unless we gain access to what makes life possible, the obscure truth. But at what price? Everything in the task of human existence is rationally sorted out outside the boundaries of the self, therefore onto a social scene, for the strange awareness of being inexplicably foreign to ourselves holds us. There is an old Greek word to convey this: nostalgia.

Can we find a means to make this audible to the technicians of the institutional, who nowadays – let us never forget the new legitimacy to govern – make it their métier to tell and proclaim the reason to live In the Name of Sciences? Other than the poetic arts in their various forms and in all latitudes, I see no such way.

May the reader of the website allow me a reminiscence, a sort of apologue in this regard.

As I visited Borges, we came to mention my writings and I had to read to him a text titled ‘Haute Mère’. The blind man then led me into the room where his mother had died… Next to the Bed in full splendor an unfamiliar conversation took place.

Today I recall this mythological scene, still fresh in mind. I dedicate it to those who still dare to wonder In the Name of What one does work, and to interrogate the inaugural in all life. No one could turn from this undoubtedly genealogical truth without throwing away life itself.

My experience as an historian had been the fervent connection with a past which in truth was not mine. To aspire to psychoanalysis is an alternative way to revitalize memory. The attempt, naïve at first, to go behind the scenes of a subjective past was my trial by fire, so to speak, for what was to unfold over time was the battlefield or even that Hell of having to come close to core truth. One has to fight for oneself before giving of oneself …

As to getting intoxicated with the drugs of abstraction, with the headlong rush to scientism… or worse, this had never been my inclination. My work as an analyst was also that of a casuist, whose task was to enliven clinical practice with an hermeneutics that escaped the flock of ideologues : to introduce the question of the institution into clinical practice, to establish that the abyss of the unconscious is the delirious crucible of Reason, so that the mutual bond between subject and society becomes comprehensible again.

As with all innovations in thought, as with all great ideas, so it is with psychoanalysis ; one has to recall, as Schopenhauer following Goethe reminds us, their inexorable destiny: they shall be marked as mere episodes.

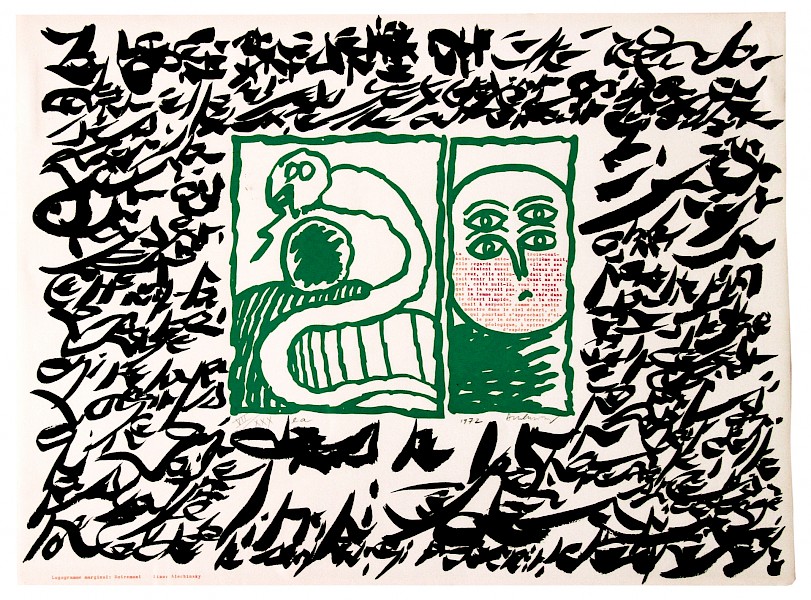

As the poets are the ones who get the common language flowing, here is a perspective upon the fortress of the subject. It offers a radical but necessary change of scenery for the passerby eager to sense the opaqueness of the concept of the unconscious, as unwittingly depicted and put in place by the cryptic inscriptions of the painter Alechinsky.

This tableau, extolling both desire and phallic metaphor, in the manner of One Thousand and One Nights, spells out its central enigma in a breathless text :

“When the three-hundred and sixty-seventh night had come, she looked ahead and her eyes were as beautiful as his eyes, as she waited for him to come to her. As for the serpent that night …”

Read what follows, and meditate upon it.

Let us finally close the circle of meaning with the following. The work of the painter carves a path towards the Unknown, through a materialized achievement. This third space of the tableau becomes an external scene for its creator, but also a mythological one embedded within a social apparatus. It draws in the anonymous public and addresses itself to anyone.

It is by means of this alienation in fiction displayed in a tableau that whoever sees it finds his own reflection in the mask of the artist, who unwittingly exhibits his unknown. Hence the encounter with a work leaves no one unscathed : for a brief moment one is half oneself, half another.

This is the truly overlooked dimension – the truth that resides behind the scenes of the subject – of the so called “cultural” approach to museum attendance, where a certain game is played out, celebrating the juggling act of the artist with phantasm.

Text inscribed on the cheeks of the subject :

When the three-hundred and sixty-seventh night had come, she looked ahead and her eyes were as beautiful as his eyes, as she waited for him to come to her. As for the serpent, that night, you see one who did not see her, who does not see the naked woman hidden in the limpid desert, who looked for her snaking through the empty sky like a monstrous marionette and who nevertheless approached her in earthly, geological desire, in the loops of hope.

Translated by Peter Goodrich, with the collaboration of Vincent Bleuse